When 2001: A Space Odyssey was released in 1968, it was hailed as a tremendous step forward for both the genre of science fiction and cinematic technology as a whole. It was a hugely ambitious film, whose delicate mixture of wonder and terror reflected the feelings of the American audience towards the Space Race, and the tantalizing scientific possibilities associated with it. While Kubrick’s sci-fi opus remains one of cinema’s most influential films, the genre itself would evolve past the idealistic outlooks of the 1960s to reflect the socio-political attitudes of a changing audience. Ridley Scott’s Alien was emblematic of this tonal shift, sharing the terror of 2001’s deep space journey, while grounding the setting in an aesthetic that the seventies audience would appreciate. This setting evoked the blue collar, rust belt industrial settings that were common to both America and Ridley Scott’s home country of England during the economically depressed seventies. Yet, just like 2001: A Space Odyssey before it, Alien has remained influential for decades after the trends, both socio-political and aesthetic, that created it.

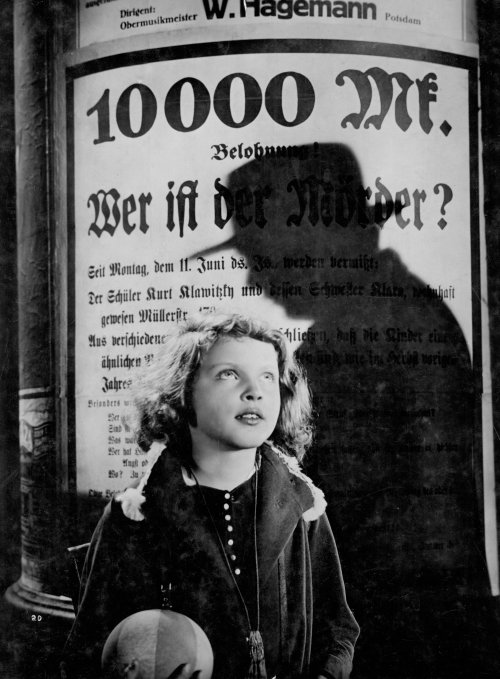

Alien is an incredible film in many ways, but its strongest quality is how well it manages to build atmosphere. The first third of Alien is deliberate and carefully constructed, as we are introduced to a cast of mostly ordinary, working class miners, tasked with recovering a mysterious distress signal on a dangerous and uninhabitable planet. In its first act the film takes its time to establish its setting and characters. These ordinary domestic scenes will stand in stark contrast to the gory horror that dominates the film’s other two acts. The thoughtful first act also gives the audience the chance to appreciate the film’s expansive and creatively realized effects and sets, from the iconic opening shot of the spaceship Nostromo, to the eerie sequence where the crew lands on the surface of the mysterious planet and approaches the surreal, abandoned alien ship. While the pace of these scenes is pretty slow, they’re remarkably effective at building tension for the arrival of the titular Alien.

When the Alien finally reveals itself, Alien transforms from a clinical science fiction film into the horror movie it’s popularly remembered as. From establishing mood and setting, the film switches gears to one tense set piece after another, as the crew engages in a desperate and one-sided battle with the monster. The domestic setting of the Nostromo turns into a terrifying maze, where the darkness and smoke of the ship’s industrial design provide ample camouflage for the monster. The late HR Giger’s design for the Alien has become iconic in its own right, a truly unique vision of terror that’s become the defining piece of visual iconography from the franchise. The film’s quality isn’t only due to production design however; Scott’s direction subtly increases in intensity with the pace of the film, leading to one of the most exhilarating climaxes in cinematic history.Alien isn’t only memorable for its visual spectacle, however. While the cast of characters aren’t the deepest in the genre’s history, the personal journey of the protagonist Officer Ripley (played with a cool resolve by Sigourney Weaver) is still highly engaging. Like the rest of the crew, she has been wrapped up in a corporate conspiracy whose implications stretch beyond the scope of the immediate plot. The film’s twist, in which the entire crew is revealed as a disposable sacrifice so that their corporate bosses can capture the alien, is a strong allegory for a beleaguered seventies working class put under increasing pressure from ever-growing corporations. Thus, Ridley’s final confrontation with the Alien is not only a cathartic battle for her own survival, but also a moment where she overcomes the corporate conspiracy that had caused the disaster to begin with. Alien is proof that an economical narrative can still convey several layers of meaning, and it’s these underlying themes that have made Alien one of the most influential horror and science fiction movies of all time.